Encyclopedia search

Sitting comfortably on the floor, Player A holds Player B as one would hold a small child in their arms. Find the common breath and release into each other’s bodies. Player A gently rocks and strokes Player B, while singing an improvised gibberish lullaby. Finish in silence. Trade roles.

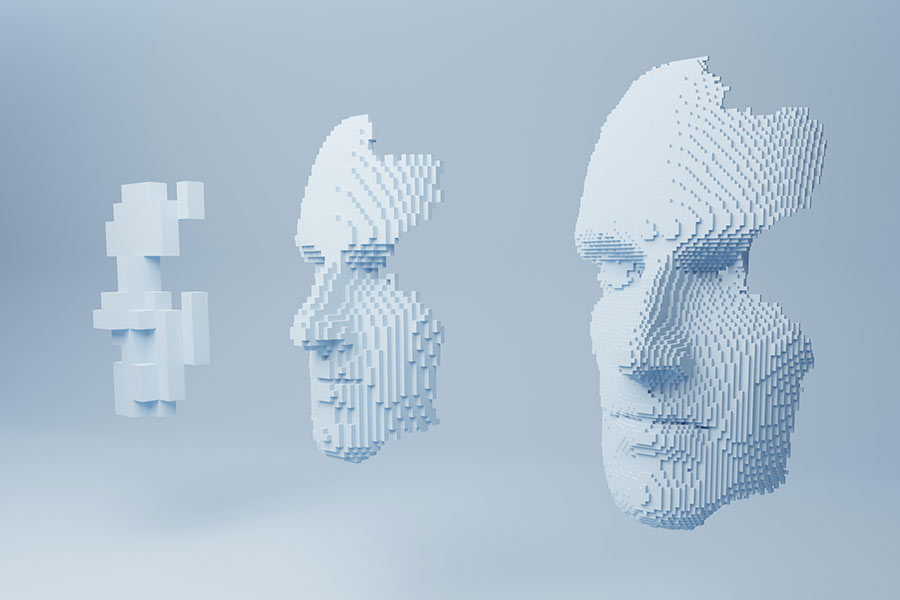

One of the joys of being an actor is the process of creating a character. Here are some common elements that help to define who a character is.

Life without relationships is like solitary confinement. We’re hard-wired to connect with each other, even when we play in fiction. We engage in make believe the same way we do in life—through relationships.

Play a scene in which you respond to each offer that the spect makes by establishing credit or blame, being emotionally changed, or treating it as though there is an ulterior motive behind the offer.

Offers carry more weight when they connect to the characters in the scene. You raise the stakes of an offer by assuming that a character is responsible and deserves either the credit or the blame.

In your training journal, write a list of all the unhelpful things that your inner critic says inside your head. On a different page, make a list of things that you’d rather hear from a coach. Tear out the critic’s list and burn it. Review the coach’s list whenever the critic shows up.

One way to get spects to do things is to instruct them. When the instructions are delivered out of story, this is called cueing. Cueing can be done with hidden notes, verbal offstage instructions , or by secretly whispering to spects while on stage.

When one offer makes another offer seem untrue, that’s a block.

The inner critic is a voice that sits in the back of your head and inhibits your impulses. In real life, this can be a good thing because it keeps you within the good graces of polite society. But when you play, the inner critic’s feedback isn’t nearly as helpful. It blocks your brain, locks your body, and offers up advice like, “That’s a stupid idea.”